CHAPTER VIII

FROM 1861 TO 1875

WE have now come to the last section of this first period of the Bonin history. The year 1861 is the date when from newly-opened Japan the first attempt is made to recover her long lost hold on the islands, and 187'5 the date when her hold on them is eventually established.

Towards the end of the year 1861, a Japanese steamer was despatched to Port Lloyd from Yedo, as the city of Tokyo was originally called, having on board a commissioner, subordinate officers, and about a hundred colonists. On his arrival, the commissioner proceeded to draw up rules and regulations for the governance of the settlers-including of course those whom he found in possession and whom it was naturally, in the first instance, greatly in the Japanese interest to conciliate. We have a copy of the following statement made about himself to the Chief Commissioner by Nathaniel Savory:

"PEEL ISLAND (Bonin),

"March 20th, 1862.

"This is to certify that I Nathaniel Savory was born 31 of July 1794 in the Town of Bradford County of Essex State of Massachusetts, U.S.A. That in May 1830 at the Island of Oahu I in company with four other white men and a party of natives fitted out and emigrated to this Island arriving here the 26 of June and commenced a settlement and with the exception of a voyage to Manila have been here ever since. I have five children viz. Agnes Burbank born Feb. 14th 1853, Horace Perry born April 3rd 1855, Helen Jane born Feb. 28th 1857, Robert Nathaniel born March 18th, 1860, Esther Thurlow born March 26th ? 1862. My wife is a native of Guam, is 34 years of age. My expectations are to remain here for life. Since the arrival of the Japanese authorities I have been treated with respect and much friendship. To the Chief Commissioner in particular for the very kind manner which he has been pleased to treat me I return him my sincere thanks.

"Respectfully, your obedient servant,

"N. SAVORY.

"In 1854 I was elected Chief Magistrate of this Island for two years which period I served and was re-elected for three years more. I served my term and declined. Since that time we had no form of government until the present regulations published by the Commissioner the Representative of the Japanese Government.

hNATHANIEL SAVORY.

"HIS EXCELLENCY CHIEF COMMISSIONER."

Mr. Russell Robertson also gives us in his paper read before the Asiatic Society these three of what he terms "the somewhat unintelligible Articles" of the Harbour regulations which were drawn up in English:

"Article 3. It shall be unlawful for any vessel or vessels that may be come into this port to discharge any of the cannon that will hurtful for the fishing,

"Article 4. Any vessel or vessels that may come into this port or harbour, the said vessel shall pay the pilot the amount of the established pilotage.

"Article 5. If any person or persons come on shore from any vessel that may be come into this port who shall have pleasure hunting and waste upon the land of any inhabitants and also) committed any of such, he or they shall be seized and transported to the Captain of their vessel."

Communication would appear to have been kept up with Port Lloyd from Japan from time to time during 1862, for it is recorded that the colonists, soon wearying of the enterprise, left Port Lloyd in batches until, early in 1863, the commissioner himself withdrew, taking with him the few remaining Japanese who had for some fifteen months cast their lot upon the islands.

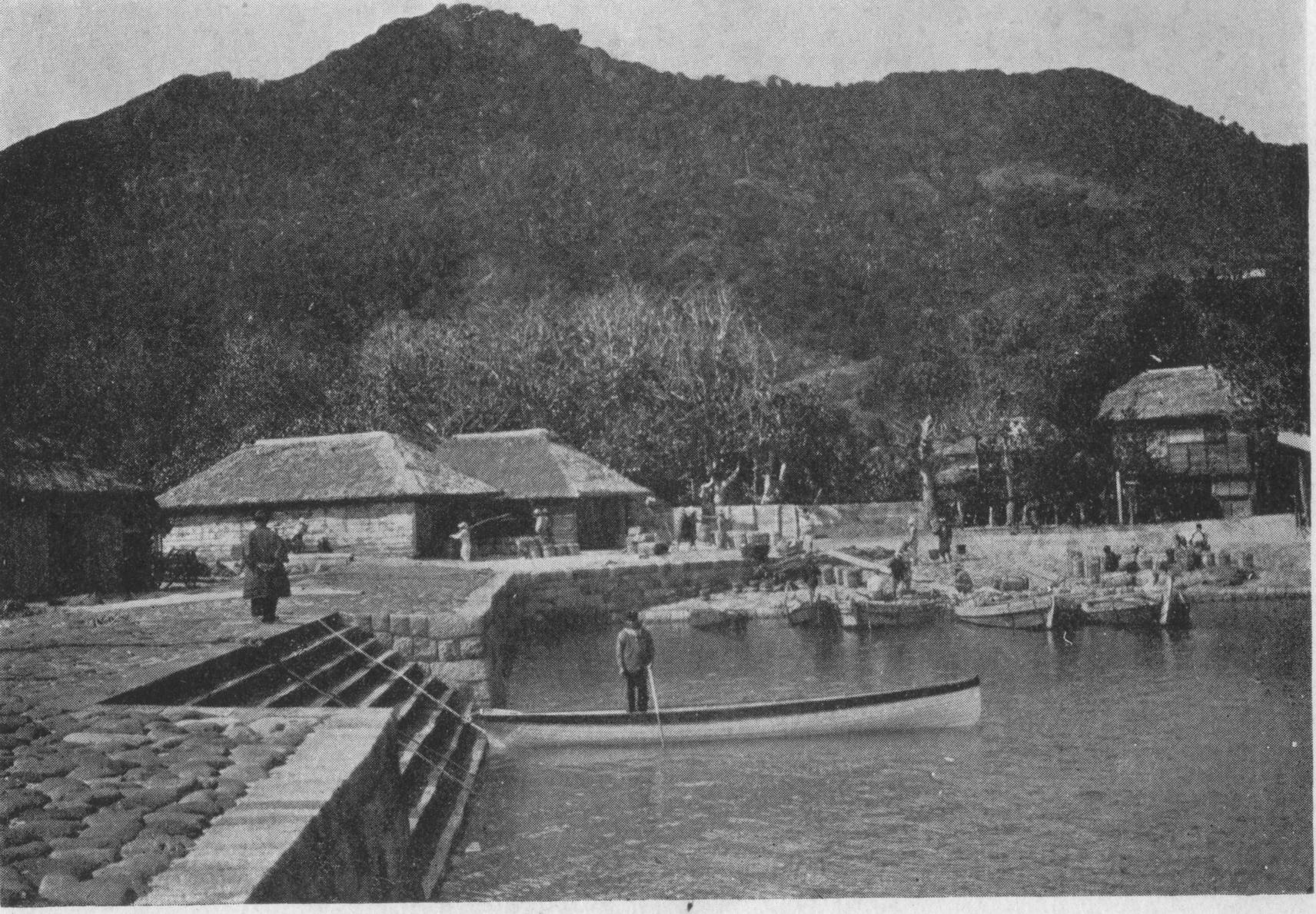

On the South side of the harbour, where the Japanese settlement was situated, may be seen to-day an imposing monument--a slab of slate-coloured stone, set up on a substantial base, recording in Japanese characters that these islands were first visited in the time of Iyeyasu by Ogasawara Sadamori; that in 1593 they received the name of Ogasawarajima (shima= island); that they were again visited in 1828 (this I think is a politic fiction, so far as it is intended to refer to a Japanese visit); that they are Japanese territory, and were visited again in 1861.

After the departure of the Japanese commissioner and the Japanese colonists, things on the island reverted very much to their former condition, and there was no one to challenge Nathaniel's virtual supremacy which he now enjoyed until the day of his death.

The last batch of letters and papers, which I give in a separate chapter, belong to this period and from them we learn in a fragmentary way of strange happenings and strange characters. Amongst others they introduce us to a man called Richards, a trader connected with Guam, and, as will appear afterwards, a very bad lot, who had so far insinuated himself into the old man Savory's trust that he made proposals of entering into partnership with him and of marrying his eldest daughter Agnes. Another man who stands out prominently in these letters is Benjamin Pease, the husband of Susan Robinson whose elder sister was the wife of Thomas Webb. This Benjamin, or Captain, Pease as he is generally called was, in his turn, one of the darkest (or "blackest") characters who ever came to the islands, and it will be seen how he had a deeprooted hatred of the Savory's and harboured designs against the old man's life. He himself is believed to have met with a violent death. He disappeared on October 9, 1874, a negro called Spencer being strongly suspected of having been his assassin.

It will be in place here if I give another typical, but a more complicated, story of contested possession such as that related in the last chapter of George Robinson and James Moitley on the South Island. In the present case the parties were Thomas Webb and a Frenchman called Leseur, with whom I myself latterly had much to do; and the trouble arose through Webb's too implicitly trusting to the friendly offices of this same Benjamin Peace.

Thomas Webb, after Nathaniel Savory, was the man of greatest consequence on the island. He had the advantage of being a scholar; and, being the possessor of a Bible and perhaps of an English Prayer Book, was generally called on to perform the rites of baptism and burial. He had already been on the island twenty-two years when on April 23, 1869, the brig Pioneer, commanded by a man called Hayes and with Benjamin Peace, who would appear to have been its owner, on board, came into Port Lloyd. Peace played the part of a gentleman with large interests' in various concerns. A friendship sprang up between him and Webb and he told Webb that he could offer him good employment on the Island of Ascension, one of the Caroline group, where saw-mills were about to be established under the proprietorship of the Pacific Trading Co., which had an agency in Shanghai. The machinery was to arrive in due course in the schooner Lizzie Allen. Webb as superintendent--apparently Peace could insure his appointment--was to receive 800 dollars. Relying on these assurances Webb was tempted to quit his holding, leaving John Marquesas in charge--the same gentleman who, we remember, had accompanied the exploring party on the occasion of Commodore Perry's visit--to place all his stock at Pease's disposal and to go on board the Pioneer with his wife and family. Before departure Pease married Susan Robinson, and the whole party set sail for the Island of the Ascension. On arrival Webb and his family were put on shore, but, having made show of giving him full instructions, Peace himself professed to have business which compelled him to continue on his cruise.

From a letter to Nathaniel Savory in the collection that follows dated February 21, 1870, written from the Island of the Ascension and signed by Gustav and Lizzie Brown, we gather that there certainly was a Company at Shanghai concerned in a timber business on the island, for Gustav Brown was himself employed in some capacity under the manager of it, and he makes mention of the Lizzie Allen as being at the time of writing overdue. But in the letter, strangely enough, there is no reference made to Webb and his family. Webb, lured away from the Bonins by false promises, had in any case secured no appointment and had been only able to make a precarious living. Benjamin Pease turned up again in due course, explained away, as well as he could, his failure to make his promises good, and eventually himself took Webb and his family on board the Pioneer back to the Bonins after an absence from them of fifteen months.

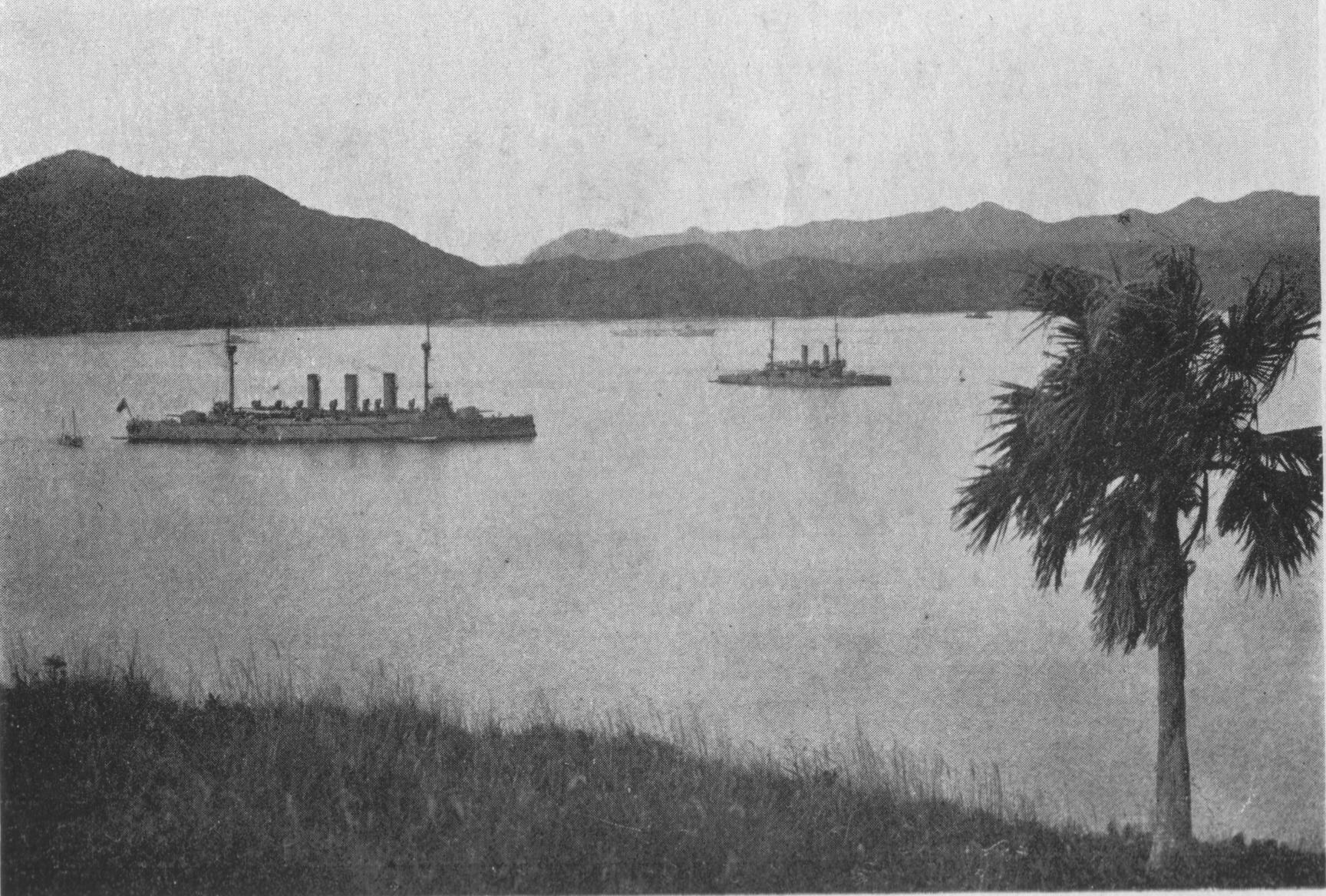

On his return, Webb found the Frenchman Leseur in possession of his holding. It is impossible in all these cases to get at the true facts and to determine who was in the right and who was in the wrong, but briefly what had happened was this: Before Webb's departure, Leseur had been on the island some four years. The chief part of Webb's holding had formerly belonged to Millinchamp, who, as related in a former chapter, had withdrawn to the Island of Guam. It would seem that Millinchamp had never abandoned his right of tenure, so, after Webb's departure, Leseur had contrived to go to Guam and had there purchased from Millinchamp the holding to which it was assumed Webb was not likely to return. Leseur had thus good ground to assert his right of ownership. On the other hand, Webb's title to his holding had been formally ratified by the Japanese Commissioners who, satisfied probably with the nine-tenths of the law, knew nothing about the other one-tenth that might upset it. Great altercations took place, and Webb, being a penman, made appeal in writing to the British Consul at Yokohama, in which he strongly denounced both Leseur and Millinchamp. The matter was eventually settled by a compromise, and when Mr. Robertson, the British Consul, came to the Bonins in 1875, he found that the rancour had died down and that Leseur and Webb were on comparatively friendly terms.

Before passing on to the Letters in the next chapter I must here give brief account of a tidal wave, or "borras" as the Bonin settlers term it, which visited the island in the autumn of 1872, and in which the whole collection of papers narrowly escaped destruction.

It occurred on a Sunday about midnight and was preceded by a severe earthquake. The sea was calm at the time, and the people were just recovering from the shock, and had gone to bed again, when old Savory heard the rush of water through the wood, intervening between the beach and the settlers' tenements, and gave the alarm. There seems to have been a succession of some six or seven waves, increasing and decreasing in force, so that the middle one was the most violent. The people clambered up the steep rock in the rear of their houses, coming down in the interval of the waves to save all they could. The letters happened to be in a seaman's chest which was rescued, but a large diary, kept by Nathaniel Savory, which with other books lived on a table set against the wall, was unfortunately swept over and ruined.