A SUPPLEMENTARY CHAPTER

In

which a short account is given of the Islands after their appropriation by the Japanese,

and of the opening of St. George's Church

FROM the year 1876 until 1904 when, under

the Revised Treaties foreigners secured the right of travel and residence in

any part of the Japanese Empire, no new settlers other than Japanese could make

their home on the Bonin Islands. Japanese settlers were slow in coming, and for

the first two or three years the Japanese colony did not prosper. But there was

to be no more withdrawal, and, after the Government had set things in some

order and made life under Japanese conditions more possible, emigration to the

islands became even too popular.

The Japanese

are happiest in a warm climate; fish is one of the staples of their food; fish

were to be had in abundance; and granted that the vessels from Japan brought

sufficiency of rice, the frugal, industrious Japanese--always attracted too by

novel enterprises--were nothing loth to try their fortunes in this new field.

The two chief

islands are no longer "Peel" Island and "Bailey" Island. As

newer maps and charts supersede the old ones, the names given by Captain

Beechey will gradually disappear and be forgotten. "Peel" Island is

now Chichijima, Father Island; its harbour Futami

; "Bailey" Island is Hahajima,

or Mother Island, and on each of these islands to-day is a population of

roughly three thousand. The original settlers--and I must not omit mentioning

that they have all become naturalized citizens of Japan--thus found themselves

every year more and more environed by Japanese. They have profited much by

being under government; by the regular service of steamers; by the laying out

of the little harbour town with its stores; by the construction of roads, and

by other facilities offered them. On the other hand they had lost their freedom

and independence of action, so far as they were no longer their own masters,

and had to submit to the growing domination of the Japanese. They have watched

the goats and turtles disappearing, and fish becoming procurable only in the

open sea; they could make no protest against the ruthless clearings, the

wholesale cutting down of trees; nor check the keen competition of the

Japanese, one with the other, and all with themselves, to derive from the

islands all the immediate profit they could; and it must be said in pity for

the islands, that almost all the Japanese who have gone there, as farmers and

cultivators, have gone there without any capital.

Hahajima, or

the South Island, is mainly peopled by workers on the sugar farms, but

Chichijima, though it has the smaller population, is an island of altogether

greater consequence. This is due, of course, to its fine harbour. On Chichijima

to-day there is the Government House with its staff of secretaries and clerks,

the headquarters of the island police, the post office, the school with its

certificated teachers from Japan, the office of the steamship company, a

canning factory, etc. But this harbour island has further become a telegraph station,

for when the island of Guam had been ceded to the United States after the war

with Spain, cable connexion was established between that island and Hawaii, and

latterly, in 1906, the cable was carried through Chichijima to Japan. As a

telegraph station the island must be permanently of some importance and,

because of this telegraphic connexion with the mainland a meteorological

observatory (or "station") has also been established on the island.

The production

of sugar is the chief industry, and bananas are largely cultivated; but hardly

a year passes without serious damage being wrought by the typhoons. Another

industry, which has furnished considerable employment for the women, is the

making of soft white plaited baskets from the long ribbon leaves of the Lohala

palm; handles are given to them and they are fastened with bits of shell or

coral which pass through a loop. A company has secured the monopoly of this

trade, and while the baskets, strangely enough, may be purchased in towns in

England and elsewhere, they will not be found in the shops in Japan.

For many years

the stalwart men-settlers made their living chiefly by seal-hunting, but this

is a pursuit which is unfortunately no longer open to them. They were engaged

by companies, and left the island to join their sealing schooners, at Yokohama,

or Hakodate, generally in March, to return in October or November. If they had

average luck, a hunter would bring back the equivalent of about 40 or 50.

A mail steamer

of some 2000 tons now goes to the islands from Yokohama twice a month. Formerly

little steamers of not half that tonnage made the voyage in alternate months,

but when the seas ran high they were greatly delayed. Moreover, 160 miles out

from Yokohama there is the large island of Hachijo with rocky inhospitable

shores, and here the steamers have to discharge and take in cargo. I remember

once, in one of my earlier visits, how the high seas and strong currents round

Hachijo fairly baffled us, and our little steamer having shifted from one side

of the island to the other, had at last to give up in despair and make back for

Yokohama.

It would be

worth very little to say that on the whole, and all things considered, the

relations between our settler friends and the Japanese have been as amicable as

could have been reasonably expected; for the relations, under the circumstances

that had thrown them together, and taking into account their strangely

differing characteristics, would have furnished scope for a most interesting

psychological study. But with the general statement, made above, we must for

the present content ourselves.

Where I think the Japanese certainly failed

from the first in their duty towards the settlers was in making no provision

for teaching their children the elements of English. This was a boon they might

easily have conferred upon them. Latterly this defect was supplied by the

opening of a mission school, presided over by Joseph Gonzales, and many of the

Japanese were not slow to avail themselves of the opportunity thus offered for

their own children. To-day the children of our settlers go as a matter of

course to the Japanese elementary school, but we must bear in mind that many of

the men, Mr. Gonzales included, have married Japanese wives, and the children

of such marriages are hardly distinguishable from Japanese.

After Japan's

two victorious wars against China and Russia, the Bonins were just a place

where national pride was likely to display itself too arrogantly, and

missionaries who came to the islands could not fail here and there to be

unfavourably impressed with the bearing of the people. But having said this, I

gladly acknowledge that we have met with so much compensating friendliness that

our stays on the island have always been pleasurable. By the Governor we have

never been otherwise than courteously welcomed, and no obstacles of any kind

have been put in the way of our missionary work.

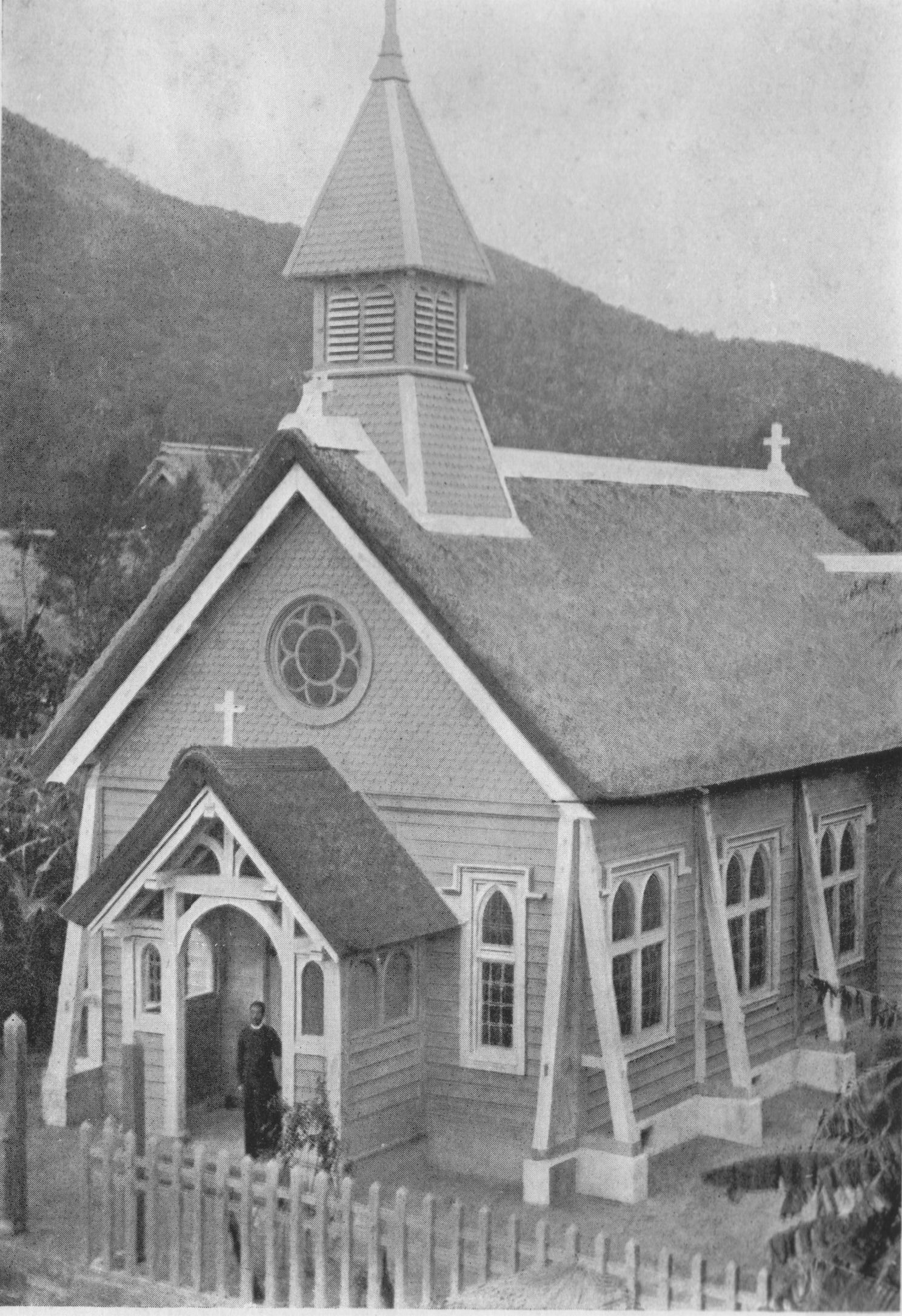

The occasion of

the opening of S. Georgefs Church on Sunday, October 17, 1909, was a memorable

one. The church had been specially designed by Mr. Josiah Conder, F.R.I.B.A.,

of Tokyo, to whom our debt of gratitude was largely increased for undertaking,

under necessarily difficult conditions, the work of its erection and its internal

furnishing. It is a wooden structure on a solid concrete foundation, with a

deeply thatched roof of cabbage palm. A rose window at the west end was

appropriately the gift of the S. Georgefs Societies in Yokohama and Kobe. The

other windows with their stained glass designs were the generous gift of the

architect himself. On the Tuesday previous to the consecration of the Church by

Bishop Cecil,[1] we incvited

all the chief people in and around the little town to a reception in the Church

frounds. The refreshments had been put in the hands of a caterer in Yokohama,

and the party had to be a little accelerated for fear lest certain of the good

things should spoil, and the ice for the ice-creams should melt away. The

gathering was a most successful one, and a speech was made by the Governor, Mr.

Ari Kotaro, to which the Bishop replied. Post cards with a picture of the

Church were distributed to all the guests, and the master of the post-office

kindly allowed them to be postmarked with the date.

There had been

suggestion that the Church should receive the name of St. Nathanael or of St.

Bartholomew, who has been generally identified with him, but there were not a

few minor considerations which tended to confirm our eventual decision to

commemorate the fact that the Bonins had once in the name of King George IV

been claimed for England, by dedicating the first Church on the islands to

Englandfs patron saint.